How can we move past reductive understandings of identity and work toward becoming better allies? Here are a few golden rules for allyship.

1. Ally is a verb, not a noun.

You can ally for marginalized communities, but that does not make you an ally. That’s because “being an ally” is about the journey. It’s a destination that is always just over the horizon. It’s not a location that you can plant your flag in the sand and declare “I did it! I’m here! I’m an ally!”

2: The only thing you can control is how you react when you make mistakes.

Everyone wants to believe that they’re a good person, and it’s painful to think about how you may have harmed people. But the reality is that no one is perfect, and making mistakes is inevitable, so let go of your fear that you’ll screw up because you will. What you can control is how you react when you are made aware that you have made a mistake.

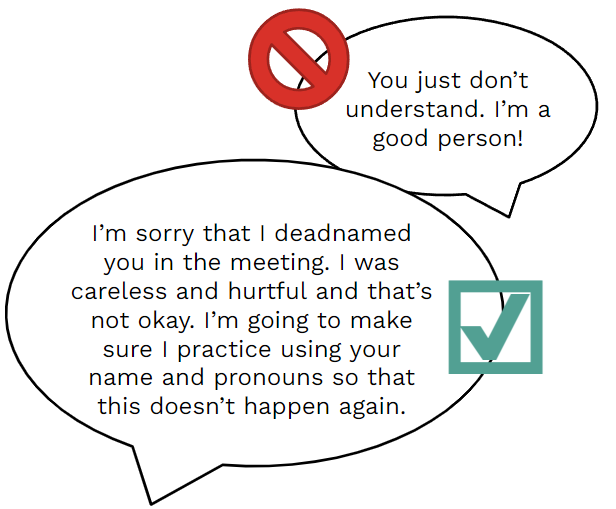

When someone tells you that you have hurt them, that is not the time to insist that you’re a good person. Nor is it the time to explain that you didn’t mean it, or that they took it the wrong way. Because you don’t get to decide someone else’s reality.

Be accountable. Apologize (a good one, and not just an ‘I’m sorry you were offended’ or ‘I’m sorry that you feel that way’), acknowledge the harm that was caused, and take action to make sure the mistake isn’t repeated.

Also, it’s important to remember that someone telling you that you hurt them isn’t an attack. It’s a gift – an expression of trust and an attempt to preserve the relationship that was damaged by your harmful actions instead of cutting ties to avoid future repetitions of that harm.

3. Don’t center your discomfort over someone’s lived experience of harm.

The pain of being told that you said something racist is not the same as experiencing racism.

It’s very common for people with privilege to get uncomfortable and defensive during discussions of marginalizations that they don’t experience. This can look like white people feeling uncomfortable discussing racism, cisgender people feeling uncomfortable discussing transphobia, or abled people feeling uncomfortable discussing ableism and disabled rights. Again, no one likes to feel like they are a bad or harmful person. And when you’re used to living a life in which you are accustomed to not thinking about your privilege, being asked to confront it can feel extremely painful.

The problem is when privilege causes us to equate the pain of sitting with unexamined privilege with the lasting lifelong harms experienced by marginalized people. For example, a white woman who cries over her distress about being told she said something racist should never be prioritized over a person of colour who lives the trauma and stress of experiencing racism on a daily basis. And yet, because people with privilege tend to hold more power in social interactions, it is often easy for people with privilege to use their power to derail, shut down, and avoid discussions that make them feel uncomfortable.

This can also happen when discussing issues of marginalization on a more general level. It’s very common for some men to interrupt discussions of gender equality by insisting “not all men”. But demanding that someone acknowledge that “not all men” is harmful is another way of prioritizing your feelings of comfort over the lived experiences of people experiencing gender oppression.

It’s okay to feel uncomfortable around these discussions. But rather than letting that discomfort make you defensive, effective allyship is being quiet and listening to what is being said, and then really reflecting on what you’ve heard later.